Music

Music

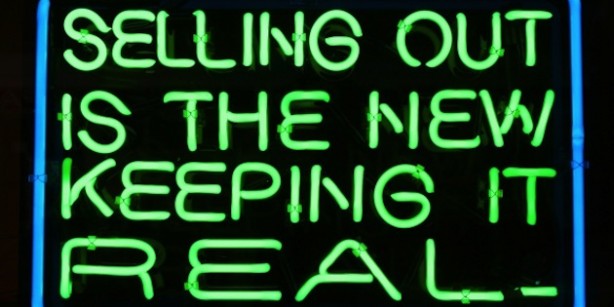

Is selling out really "saving indie rock"?

by Mark Teo

November 11, 2013

Most artists want to create honest art, but they also want to make an honest living.

Yesterday, Buzzfeed, in a rare-but-increasingly common foray into longform, dropped a bomb: They argued that “selling out,” namely by licensing music to commercial advertisements, has “saved indie rock.” The basic idea? Due a collapsing music industry—where album sales net meagre earnings and the touring machine, including merch sales, can’t compensate for basic costs—music is becoming increasingly hard to monetize. This we know is true.

Buzzfeed’s story, however, argues that the corporate world has provided much-needed cash to music’s perpetually starving artists. Their examples? The story opens with Tegan and Sara playing an ad agency; Lorde’s involvement with Samsung is cited; fun. lent their song to a car commercial; Matt and Kim talk about how branded work has helped fund their artistic dreams; and members of Midlake and the Twilight Sad contribute to Black Iris, an indie-rock centred agency geared at creating commercial jingles.

As a result, Buzzfeed argues, brands have become the new labels. “I’m seeing baby bands talk about advertising the way that baby bands used to talk about getting signed, which is very interesting to me,” says Bryan Ray Turcotte, a partner at Beta Control, an agency geared at providing, licensing, and distributing commercial music. “It’s like the in-house music producers are the new A&R guys, and the bands want an ad, just the way they wanted a record deal.”

But is this problematic for the independent music world? Yes and no. Indie rock’s anti-industry, D.I.Y. penchant—which Buzzfeed invariably paints as antiquated at worst, needlessly idealistic at best—isn’t simply rosy-cheeked optimism. There are very real, tangible reasons why music and commerce don’t, and can’t find a happy medium—and that’s because art and business have different goals. Fundamentally, art exists for its own sake; brands, and the marketing and messaging behind them, exist to profit. Your 13-year-old inner punk is screaming, “CAPITALISM, SHEEPLE!!” And he or she might be right.

To that end, artists who lend their songs to commercials are at a real risk of denting their cred: Art lent to—or worse, written for—commercial purposes is compromised. Because a good song isn’t just a good song: As listeners, we wonder about its intent, its authenticity, its original purpose. We might still like Feist after she lent her song to an Apple commercial, but that’s because we assume it wasn’t written explicitly for an Apple commercial. On the other hand, would anyone outside of the corporate marketing world ever listen to Black Iris’s music?

When we question an artist’s intentions, we also question their art—it’s why debates range around the neo-nazi imagery of Death in June or the marketing-friendly music of Walk Off the Earth. No one questions Fugazi’s motives.

The issue isn’t as simple as REAL ARTISTS =/= COMMERCIAL MUSIC. Because while most artists want to create honest art, they also want to make an honest living. And while the music industry once provided an avenue (though let’s not forget: it, too, was plenty exploitative), now, even the most successful artists struggle to make ends meet. “A tiny sliver of bands are doing well,” Sara Quin told Buzzfeed. “The rest of us are just middle class, looking for a way to break through that glass ceiling.”

To that end, if brands are replacing labels and purchasing licensed music, who cares?

Once the sheen of being in a well-respected band subsides, there’re mouths to feed. So, if writing commercial jingles can help pay some dude from Midlake’s phone bills, or licensing a song can land Lorde a pretty penny, then why not? Who cares if commercials intend to use an artist’s song to leverage their cultural cachet or their fanbase? They’re paying—and artists shouldn’t have to starve for their art.

Of course, it’s a war that’s been raging on for ages: Do creative agencies produce real art, even if they’re client-commissioned? How close should advertising and editorial become? Is selling out really saving indie rock—and does indie rock need to be saved in the first place?

Tags: Music, News, lorde, Matt and Kim, selling out, Tegan and Sara