Music

Music

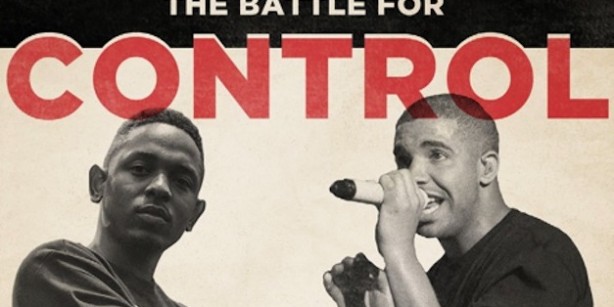

Kendrick Lamar and Drake and the battle for Control

by Richard Trapunski

August 31, 2013

If you’re even a cursory fan of rap and you haven’t been living under a rock (or at least somewhere without access to Twitter), chances are you’ve already heard those lines, committed them to memory, and read countless hyperbolic theories on what it means for hip hop:

“I’m usually homeboys with the same niggas I’m rhymin’ with but this is Hip Hop and them niggas should know what time it is. That goes for Jermaine Cole, Big K.R.I.T., Wale, Pusha T, Meek Mill, A$AP Rocky, Drake, Big Sean, Jay Electron[ica], Tyler[, the Creator], Mac Miller. I got love for you all but I’m tryin’ to murder you niggas. Trying to make sure your core fans never heard of you niggas ‘n they don’t want to hear not one more noun or verb from you niggas. What is competition? I’m trying to raise the bar high.” – Kendrick Lamar, “Control”

In the span of a couple of minutes, Kendrick Lamar hopped on a non-album track from King of the Also-Rans, Big Sean, called out a discography’s worth of his friends, young rappers at the top of their game, and caused the internet to lose its collective shit.

Critics high and low are calling it a game-changer, a propeller lifting an entire genre to new heights, and it’s already garnered a number of excited analyses, each carefully dissecting the album’s allusions (Jay Z’s “Where I’m From,” Kurupt’s “Calling Out Names”), targets, and notable omissions (Lil Wayne). But one thing that most have failed to connect: “Control” was released just one week after hip hop’s last game-changer (which in 2013 terms basically translates to “trending topic”): Drake’s 2013 edition of OVO Fest.

By now, people know what to expect from the Toronto rapper’s annual hometown love-fest: a who’s who of monumental names in rap and R&B both past and present. The rolodex-flaunting spectacle of unannounced special guests is ostensibly designed to put his city on the map, but it also fulfills the more self-serving goal of putting Drake on the map, proving that the former teen star from Forest Hill has the connections and power to reunite ‘90s R&B stars TLC, or convince an ego as big as Kanye West to play a supporting role in someone else’s variety show.

It’s hard to think of two events so similar, and yet so diametrically opposed. Both artists essentially fulfill the same function: shooting up, using the reputations of other rappers to inflate their own. But where Kendrick attempts to raise the bar high by threatening to bury his competition, Drake assembles them all in one place for high fives. In the case of the Weeknd, he even used it as an excuse to quash rumours that his 401 to 905 bromance had gone sour. It’s no surprise he’s one of the few rappers called out in Kendrick’s “Control” verse that didn’t respond, and it’s the same reason his battle with Common was so anti-climactic. Drake doesn’t do murder, he does hugs.

Both Drake and Kendrick present blueprints for rap moving forward, but one is more convincing than the other—and it’s not the one that’s been getting all the recent attention. For all the talk of Kendrick announcing himself as “the future of hip hop,” his version is actually rooted in the past. Think of the greatest rap feuds of all time. Biggie versus Tupac, Jay Z versus Nas, L’il Kim versus Foxy Brown. None of them take place later than 1999, long before arrogant sensitivity surpassed dick-waving as hip hop’s default “future” setting. A rapper calling out his peers wouldn’t have been out of the ordinary in the ‘90s, but it’s front page news in 2013 (at least for magazines like XXL and Complex).

As Grantland points out, Kendrick’s “Control” verse didn’t come out of a vacuum. It’s an overt echo of Korupt’s own gangsta rap power play, another Compton rapper lyrically invading New York. Kendrick has always been a nostalgist. His 2012 breakout good kid, m.A.A.d city uses Compton’s gangsta rap myth as source material for intricate, postmodern self-examination.

Kendrick’s “Control” verse has convinced many rappers, both dissed and not, to fire back with their own freestyles – the A$APs, and a few masterful trolls—but they’ve all generally been positive. “The nigga didn’t say nothing about nobody’s mother, he ain’t want problems,” A$AP Rocky told Hot 97, for instance. “He just said, ‘These is my niggas, and I’m letting y’all know it’s competition.’ What’s the problem? That man know I’m where he at. Hip-hop is all about the sport. It’s all about the culture.”

Competition is a great way for rappers to push each other and the genre forward. But it’s not as if classic rap battles were all in good fun. Biggie versus Tupac wasn’t fought just with nouns and verbs. It involved cuckolding, vicious threats and, depending on who you ask, literal, actual murder

So much of ‘90s rap feuding was based on geography, which is a factor that doesn’t mean as much now as it did in the halcyon days of East Coast vs. West Coast. Sure, Kendrick’s “King of New York” boast caught nearly as many tweets as his hit list of rappers, but when A$AP Rocky, one of the most prominent new batch of New Yorkers, sounds straight out of Atlanta, what exactly does that mean? When mixtapes blow up online first, who cares where it came from? Drake’s mythology is as much about his hometown as Kendrick, if not more so, but he’s not trying to encroach on anyone else’s scene; he’s drawing them all to his.

Which is why, when the dust is settled and No I.D.’s beat has become tired, that one verse won’t seem like the most monumental thing in hip hop. It’ll just be another good verse on a YouTube stream of a non-album track.

Tags: Music, News, AUX Magazine, Drake, Kendrick Lamar, Trendspotting