'Known punks' Titus Andronicus want you to support Local Business

by Mark Teo

June 18, 2013

Photo: Kyle Dean Reinford

When Titus Andronicus dropped their 2010 album, The Monitor, we all collectively made a single assumption: Patrick Stickles and co. had arrived. And why not? Somehow, The Monitor made several unthinkable paradoxes work: It was a punk rock concept album. It paired the band’s Springsteen-worshipping, Desaparecidos-owing guitar work with orchestral instrumentation. And it tackled modernity using a near-academic framework, ever so briefly making it permissible to be a Civil War history dork. Critical and public adoration, predictably, came pouring in by the bucket.

With the arrival of 2012’s Local Business, though, Titus Andronicus took yet another sharp left turn: They turned their back the melodrama that made The Monitor exceptional. Armed with a fresh Neil Young obsession and an anarchist graffiti-inspired band insignia, the band’s was reduced to its core—the band was reduced to guitars, bass and drums, with the studio addition of Owen Pallett’s violin—with Stickles using his signature snarky wordplay to tackle capitalism’s decay, the absurdity of modern marketing, and even his own eating disorder. Grandiose it ain’t, but Local Business is Titus Andronicus’s most punk rock album yet. And they’re not afraid of calling it that, either. We drove around Toronto with Stickles—who, armed with a video camera and a pack of Viceroys, came across as part demented sociology prof, part surf bud—prior to a recent performance.

On your third LP, Local Business, you elected to lean heavily on your punk-rock roots. Why did you decide to revisit your formative influences now, especially after writing an album as ambitious as The Monitor?

We already did that with our last record, and you can’t do it twice in a row. I mean, The Monitor was a punk record, but it was weird— being a concept album, it had more prog rock tropes. It wouldn’t have been logical to do a record that was [bigger-sounding] than our second one. We’d completely shot our wad, so the only thing to do was to retreat to our roots. We wanted to create something with five guys, recorded live off the floor.

Like Neil Young says, it was about taking photographs rather than painting pictures. It was about capturing moments as they occur—when something is created from nothing—rather than methodically constructing something out of nothing, like we did with The Monitor. We used lots of overdubs and click tracks on that record, and Neil Young thinks that’s the downfall of the recording industry, and after reading that his book, Shakey, I’d have to agree. So we wrote a record in tribute to Ontario’s very own Neil Young.

As a province, we’re flattered. Let’s talk, for a second, about your social media presence. You use plenty of faux-marketing speak—like calling any update a #CONTENTBLAST. Is that your way of poking fun of bands who take themselves too seriously as brands?

Yes. But I get to have my cake and eat it too. What you described is apophasis. [ED: To clarify, it’s a backhanded figure of speech, meaning “to mention without mentioning.”] It’s great for me, because I get to utilize the tools of Internet branding culture to my own selfish purposes, expanding our own brand in the process. But at the same time, I’m a known punk, so it’s clear that I’m also critical of these things. So people like you will think it’s funny, but at the same time, my brand’s expanding into new territories.

So, do you view Titus Andronicus LLC—which is what you call the band in several places—as a small business? As in, it’s your opportunity to work while making your own rules?

You could say that. We became a limited liability corporation in New Jersey, when we wanted to open a bank account and start filing tax returns. I make a big deal about it now is because yes, we’re a punk band, and as such, we’re critical of capitalism, consumerism, and bureaucracy. But we, as a business entity and individuals, exist in a capitalist system. If we separate ourselves from it completely, we will cease to survive. It’s the inherent contradiction—the albatross—that hangs around the neck of every punk band, from Crass to Good Charlotte. Rather than try to sweep it under the rug, we might as well put that out into the open.

You talk about the albatross that hangs over every punk band—is that where the nihilism on this record’s coming from? I mean, it opens with the line, “I think by now we’ve established / Everything is inherently worthless.”

It’s not nihilistic at all. It’s a message of empowerment for every human. Yes, the universe is void of inherent meaning. But in the terror of that infinite void, what freedoms we find to create our own meaning! It’s the birthright of every human, the thing that truly separates us from our animal brothers and sisters—not that it entitles us to eat them or wear their skin. So yes, I say nothing means anything because it’s the damn truth. Except in a world where nothing means anything, anything can mean everything. It’s the message of hope I pick up from the existentialists.

So, what spurred the existential line of questioning? What was going through your head when you wrote the record?

It was 2011, and there was a lot of discussion going around about income inequity— it’s not a new story, and it’s not one we’re getting any closer to the end of—especially around the rise of the Occupy Wall Street movement, which I can’t claim to be involved with at any kind of meaningful capacity. But I think if you’re a person who’s interested in the pivotal ideas of their time, it’d be hard—especially as an artist—to not consider those things. It seems like the principal political aspiration of my generation is to level the playing field, even if we have snowball’s chance in hell of getting there.

In America, we want to live in a society a lot more like your Canadian one, even if you have that income inequity, too. But you guys have that healthcare, you know? It’s stuff that everyone deserves. Here in the First World, we can satisfy that need 10 times over, but people in America think everything needs to be earned. And maybe we can’t educate everyone, but we can give people food and medicine. You guys in Canada have a much higher baseline for the quality of life.

Perhaps you’re over-romanticizing Canada. Many feel that Stephen Harper’s government is a threat to Canada’s socialized health care system and Canada’s other social programs.

I mean, it’s any government, dude! They’re all devils—obviously! But your devils, horned, cloven-hooved and pitchfork-toting as they all are, are working within an infrastructure that’s a lot more generous and human-respecting than America. That being said, I will never leave America. Man, I love America, and all you Canadians need to come down and see the shit we’re doing. It’s wild and crazy.

Oh?

Geez, you ever heard of a band named the So-So Glos from Brooklyn? Or Diarrhea Planet from Nashville? Or the Screaming Females? We got it poppin’ down in America. You wouldn’t believe the DIY scene we have in New York, it’s the best in the world. There’s regional punk scenes—you couldn’t swing a cat without hitting one, dude.

You’ve tackled consumerism on the record. Did you intentionally minimal instrumentation to mirror that fact that your lyrics rail against excess?

I hadn’t considered that. It’s true, though, that the form reflects the function. I mean, when I was writing the lyrics, I took away a lot of the metaphor. That was a reflection of the stripping down of the grandiosity of the music. More direct music, more direct language.

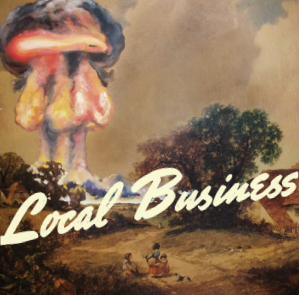

Right. So, explain the idea behind Local Business’s banned artwork (above).

It’s a pastoral landscape, with figures in the foreground—it’s these women with baskets, who live an agrarian life. Off in the distance, there’s a mushroom cloud. The thought there was, what did these women in the picture do to bring on the detonation of an atom bomb? I would argue they didn’t do anything. That’s the joke on Local Business; there is no local business, and nothing operates in a vacuum. Things can be going on miles away from here, but you’ll suffer because of it. And you can try to get away from the capitalist system, you can hide out like Thoreau, but they’ll find you.

Because, like, the enemy is everywhere, am I right?

Exactly.

This article originally appeared in the June 2013 Issue of AUX Magazine.

Download and subscribe for free in the app store.

Tags: Music, Featured, Interviews, AUX Magazine, Titus Andronicus