Film + TV

Film + TV

Deciphering the noise of Sonic Youth's 'demonlover' soundtrack

by John Semley

October 29, 2012

Film School looks at the points of contact between movies of bands, film culture, and music culture. This column originally appeared in the October issue of AUX Magazine. Download and subscribe for free on iPhone and iPad in the App Store.

The first line of Rob Mitchum’s Pitchfork review of Sonic Youth’s OST (Original Soundtrack) for the 2003 film demonlover [sic], published April 30, 2003: “I’ve come to the realization that I’m never going to figure out noise.”

It’s an honest insight, and useful in the project of understanding both demonlover, the unsettling corporate espionage/porno thriller by French filmmaker Olivier Assayas, and Sonic Youth’s accompanying demonlover OST.

Music is important to Assayas’s films. His latest stuff, 2010’s Carlos and this year’s Après Mai (I’m choosing to ignore the annoying English-language title, Something In The Air), seem like period-specific journeys through the director’s well-curated iPod, from Beefheart to Wire, The Feelies, et cetera. His commissioning of a Sonic Youth score for demonlover—a harder, nastier film than Carlos or Après Mai, or anything Assayas has made—may also smack of coolness. But it’s a different gambit altogether.

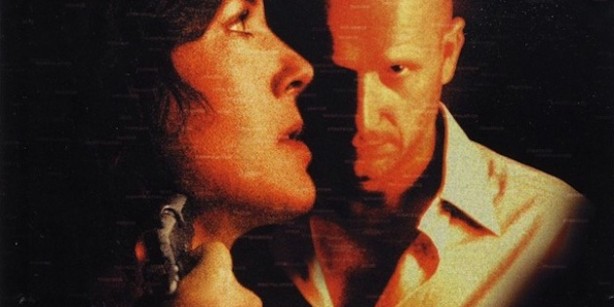

It may seem cool, getting a cool band to score your dark, disquieting movie about an online torture porn empire. And Sonic Youth’s droney, ambient, sometimes-noisy soundtrack, in combination with the presence of certified cool indie star Chloë Sevigny and certified (post-Showgirls) ironically campy-cool Gina Gershon, and palatable scenes of pixelated hentai pornography and English-language dialogue, made demonlover saleable as a cult object. demonlover’s coolness also worked in combination with the chilliness the film, and its soundtrack, cultivate.

If you’ve never seen it, demonlover works like a kind of less-good spiritual sequel to Videodrome. A chilly executive (Connie Nielsen) drugs a co-worker and jams her in a car trunk for three days, so that she may spearhead the acquisition of a Japanese pornography company specializing in 3-D titillations rendered to look like good old “state of the art” Playstation 2 graphics. While inking a similar porn distribution deal with an American company, Nielsen comes across a pirate porn site, Hellfire Club, which allows anyone with a credit card to torture real victims in real-time. A series of assaults, double-crosses, headshots, and triple-crosses transpire across Assayas’ smudged, rain-streaked canvas, until Nielsen finds herself bound-and-gagged and trapped in Hellfire Club HQ, staring into a ceiling-mounted camera and out of a computer monitor somewhere in Middle America, like she’s pleading with the viewer.

Like Michael Haneke’s annoying Funny Games, demonlover is a film about violence and desensitization that is also totally violent (if not quite as desensitizing). demonlover isn’t engineered to be enjoyed so much as endured. Awash with images of fucking, violence, and cartoon tentacle penetration, it can be tricky separating demonlover’s nauseating provocations from what’s meant to be a consideration of nauseating provocation. It can seem at times entirely noisy.

I don’t know if I can make Pitchfork’s Rob Mitchum understand noise, music-wise, something I don’t even really think I understand myself, except for I like Sonic Youth a lot and own those New York Noise comps, and even that’s probably like saying you like hip-hop while only really liking two Jay-Z albums and expensive sneakers. But what I find interesting about demonlover is how it uses its sheer torrent of images to manufacture a kind of cinematic noise, no less alienating or confusing or un-figure-out-able as Sonic Youth’s clanging score. (And, of course, that this procession of visual noise is cued to SY’s aural noise only deepens the noisiness.)

In high school, I was square in demonlover’s target demographic, i.e. kids who eat Pizza Pizza and drink beer and smoke cigarettes (and maybe some pot) and try to find “extreme” movies that also have some vague art-house edge to them, then watching them compulsively in order to cultivate the twin auras of being a.) a refined aesthete who is into foreign pictures and doesn’t balk at reading subtitles or aything; and b.) also a bit of a badass who doesn’t blink at scenes of rape or heads exploding and who treats not-squirming through these squirmy movies as an achievement in itself. demonlover (even the name was inviting, getting at that split between beauty and evil) was one of these movies. So were Ichi The Killer, the Larry Clark movies, this Kevin Smith-produced rape/revenge clown movie Vulgar, and some of David Lynch’s movies, especially Blue Velvet and Wild At Heart. (In hindsight, I’m wildly embarrassed about co-opting Blue Velvet as part of these constellations of entirely adolescent identity formulation, but at the time, drinking over-proof Molson XXX, which my friend’s sister’s fiancé swore provided a buzz on par with heroin, and then chucking the empty bottles against that same friend’s neighbour’s barn while yelling “LET’S FUUUUUUUUCKKKKKK!!!” felt like partying at the edge of the world.)

Like Blue Velvet, demonlover inserts its horny teenage viewer surrogate within the movie itself. Lynch’s movie embeds Kyle McLachlan’s perverse detective at the centre of the action, the nexus through which the film’s tides of sex, violence, and voyeurism flow. demonlover plants its proxy way late in a film—a kid who nips his parent’s credit card to register for the Hellfire Club site, then flippantly works on his homework while Nielsen’s restrained sex-slave looks on defenselessly on his computer monitor. All the coolness and noise is finally framed by the film’s first truly provocative image: some typical kid working on a science project, not even paying attention to the woman he’s paid to torture. That the scenes rhymes with the opening shot of French execs riding first class on an airplane, talking shop while a TV screen showing a string of explosions runs unnoticed in the background, and that the kid’s homework is a DNA helix model, connecting his casual attitude toward sexual violence to some grim evolutionary impulse, is the kind of thing that reveals how gifted Assayas is as a filmmaker.

More to the point, what demonlover executes is an even sterner bait-and-switch, topsy-turvying its altitudes of coolness that are accounted for by stuff likes its halfway-experimental Sonic Youth soundtrack and its modish exploitation of sex and violence. The film actively courts an audience of masochistic high schoolers, eager to prove their extreme cult flick cred, only to punish their toe-headed bloodlust. You enter eager to feel cool, and leave feeling cold. What do you expect, cool guy?

Tags: Film + TV, News, Film School, Sonic Youth